When Web3 Enters the Multi-Chain Era

As blockchain evolves toward a multi-chain architecture, isolated ecosystems are no longer an advantage. Users, assets, and applications increasingly require the ability to move seamlessly across different blockchains. In this context, blockchain bridges have become an essential infrastructure component of Web3.

At the same time, bridges are among the most complex and risk-prone parts of the blockchain stack. Any flaw in architecture or transaction verification can result in large-scale losses.

1. Overview of Blockchain Bridge Models

At its core, a bridge is a protocol or system that enables the transfer of assets or data between two independent blockchains—a specific implementation of cross-chain technology. Because blockchains cannot directly verify each other’s state, a bridge requires an intermediary mechanism to ensure that transferred value is not duplicated or fraudulently created.

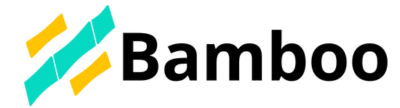

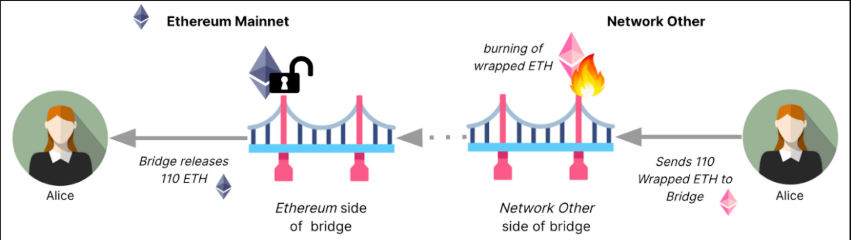

Most bridges operate around the core actions of Lock, Unlock, Mint, and Burn. When a user transfers tokens from a source chain to a destination chain, the assets are either locked or burned on the source chain, while a corresponding representation is issued on the destination chain. This process ensures that the total supply remains controlled throughout the lifecycle of a cross-chain transaction.

From an asset-handling perspective, most blockchain bridges follow similar patterns such as Lock–Mint, Burn–Mint, or Burn–Unlock. The key differences between bridges do not lie in these operations themselves, but rather in how cross-chain transactions are transmitted and verified—in other words, the relayer mechanism.

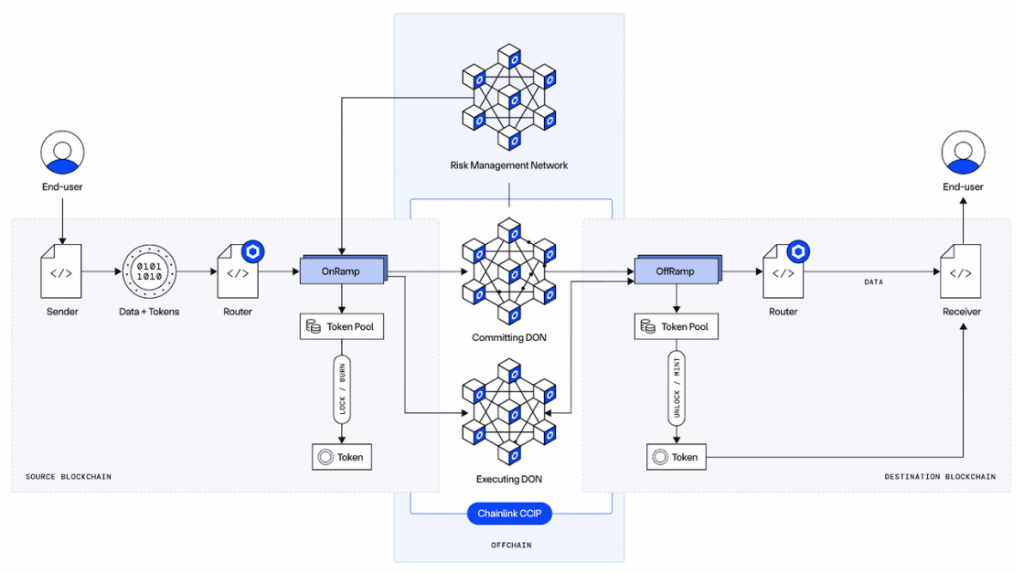

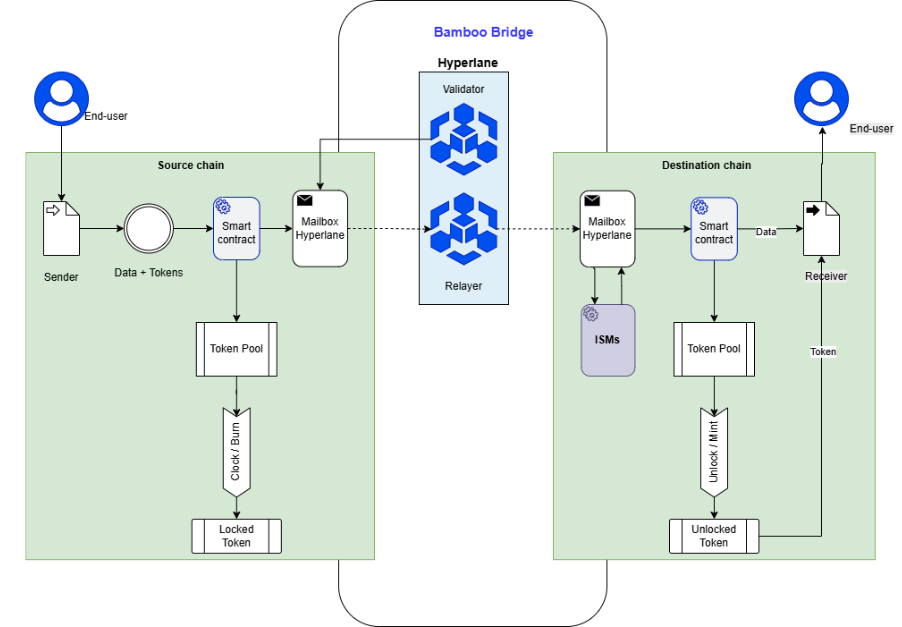

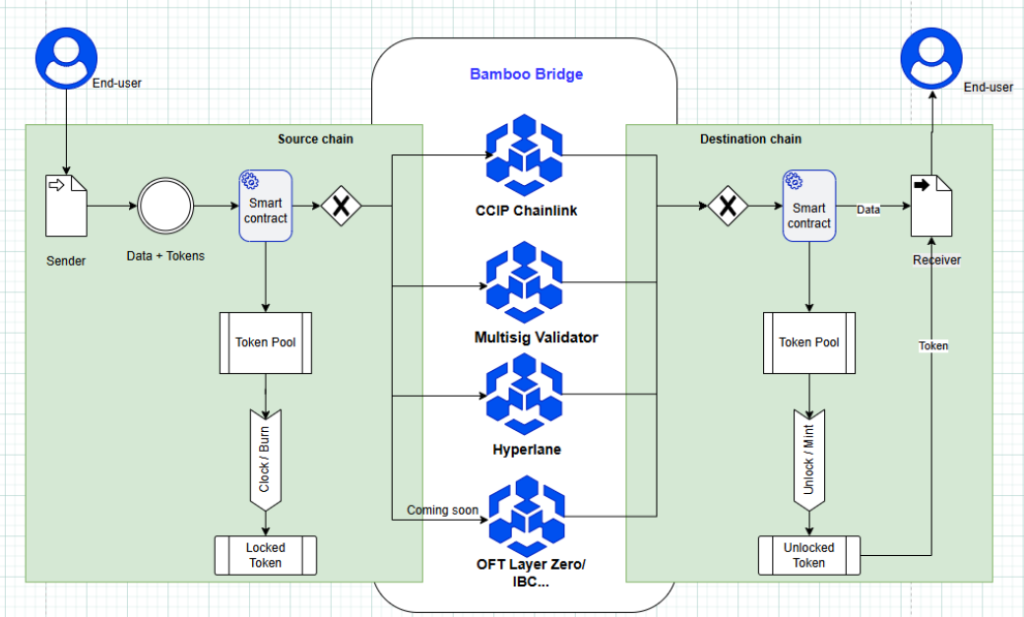

The bridge relayer is responsible for transmitting state information from the source chain to the destination chain, enabling smart contracts to execute the corresponding mint or unlock actions. Depending on the design, relayers can be implemented using various approaches, including multisig schemes, oracle networks, messaging protocols, or zero-knowledge proofs. In practice, frameworks such as CCIP, OFT (LayerZero), Hyperlane, and ZK-based bridges represent different solutions to the relayer problem, each with its own trade-offs in security, cost, complexity, and scalability.

2. How Bridges Handle Wrap, Burn, Mint, and Lock

To understand how bridges operate, it is important to distinguish the core concepts involved in cross-chain asset handling.

Wrap refers to converting a native asset into a representative version on another blockchain—for example, wrapping BTC into WBTC on Ethereum. This approach improves interoperability and asset usability but relies on a custodian or a locking contract.

Burn is the permanent destruction of tokens, typically used to signal a corresponding mint or unlock action on another chain. Burning helps prevent double-spending, but if an error occurs, the asset cannot be recovered.

Mint is the creation of new tokens based on verification that a lock or burn has occurred on the source chain. This step enables assets to circulate on the destination chain, but it is also a sensitive point if the verification mechanism is compromised.

From these primitives, two common bridge models emerge.

The Lock → Mint (Burn → Unlock) model is the most widely used today, with typical examples such as WBTC and the Polygon Bridge. In this model, native tokens are locked on the source chain, and wrapped tokens are minted on the destination chain. When transferring back, the wrapped tokens are burned and the original assets are unlocked. This model is highly flexible and can be applied to most existing tokens. However, it also creates large asset-holding contracts, increasing security risks and leading to liquidity fragmentation across different wrapped tokens.

The bidirectional Burn → Mint model is used in systems where tokens are designed with native mint and burn permissions, such as Circle’s CCTP for USDC. In this approach, tokens are burned on the source chain and minted as native tokens on the destination chain. This model improves capital efficiency and significantly reduces liquidity fragmentation. The trade-off is that it only applies to tokens controlled by issuers that explicitly support mint and burn operations.

3. Technical Bridge Approaches

Traditional Bridges

Traditional bridges operate by locking tokens on the source chain and issuing wrapped tokens on the destination chain. This approach is relatively simple but comes with notable limitations. Asset-locking contracts often hold large values, making them prime attack targets. Liquidity becomes fragmented because each bridge issues its own wrapped tokens, complicating DeFi integrations. Integration complexity and transaction costs are also high due to multiple intermediate steps.

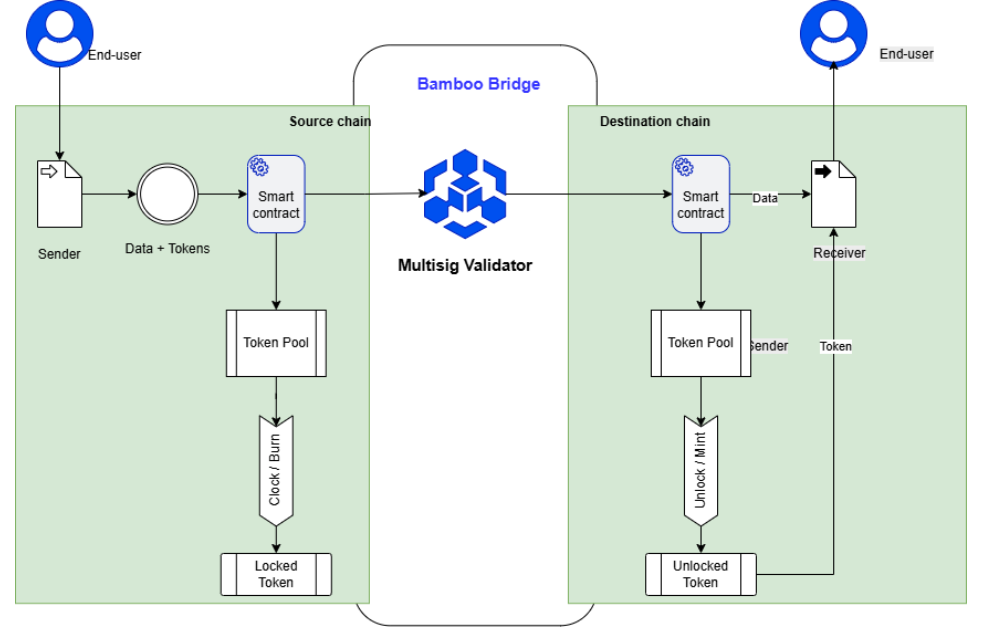

OFT – LayerZero

The OFT model by LayerZero uses a debit-and-credit mechanism, where tokens are debited on the source chain and credited on the destination chain without relying on wrapped tokens. Tokens behave like native assets across multiple chains, reducing liquidity fragmentation and enabling broader use cases such as messaging, governance, NFTs, and DeFi. In exchange, this model depends on the LayerZero endpoint and requires tokens to conform to the OFT standard.

CCIP – Chainlink

Chainlink CCIP focuses on infrastructure-level security and stability. CCIP supports multiple mechanisms such as burn-and-mint and lock-and-mint, combined with a decentralized oracle network, risk management layers, and extensive independent audits. This makes CCIP well-suited for large-scale DeFi and traditional financial applications, though deployment speed and supported token coverage are more limited.

Hyperlane

Hyperlane approaches bridging through permissionless messaging, allowing arbitrary cross-chain messages to be transmitted via permissionless mailboxes. Its Interchain Security Modules (ISM) enable customizable verification mechanisms, ranging from multisig to ZK or PoS. This design offers high flexibility and scalability but requires developers to carefully choose appropriate security configurations.

ZK Bridges

ZK bridges use zero-knowledge proofs to verify cross-chain state in a trustless manner, without relying on external validators. This approach provides very strong security guarantees, but high computational costs and implementation complexity remain significant barriers. As a result, ZK bridges are currently best suited for specialized use cases.

4. Lessons from Existing Bridges

Wormhole is one of the largest cross-chain bridges and suffered a major exploit in 2022 due to a flaw in its signature verification mechanism on Solana. The vulnerability allowed an attacker to forge cross-chain messages and mint tokens on the destination chain without locking the corresponding assets on the source chain, resulting in losses of hundreds of millions of dollars. This incident demonstrates how even a small verification flaw can have systemic consequences.

Ronin Bridge illustrates a different type of risk—operational rather than smart contract failure. In 2022, attackers compromised employee machines and gained control of 4 out of 9 validator nodes, which was sufficient to approve fraudulent transactions, leading to losses of approximately USD 625 million.

After the incident, Ronin did not immediately change its bridge architecture. Instead, it reduced majority-control risk by increasing the number of validators from 9 to 11 and fully compensated users using team reserves and a new funding round. It was not until April 2025, following a validator vote, that Ronin officially migrated from a traditional bridge model to Chainlink CCIP as an infrastructure upgrade to strengthen cross-chain security.

These cases highlight that bridges are not merely technical components, but critical infrastructure decisions with existential implications for entire ecosystems.

5. B3Bridge and Bamboo Software’s Approach

Drawing from these real-world lessons, Bamboo Software developed B3Bridge with a focus on security, reduced liquidity fragmentation, and simplified integration for Vietnam’s blockchain ecosystem.

B3Bridge adopts OFT (LayerZero) for tokens created on the platform, CCIP (Chainlink) for tokens already supported by Chainlink, and Hyperlane for other cases. As a result, OFT tokens deployed on B3Bridge can be bridged immediately without additional configuration, significantly shortening the go-to-market timeline for blockchain ecosystems.

For tokens that do not conform to the OFT standard, B3Bridge applies appropriate security mechanisms on a case-by-case basis. In upcoming articles, Bamboo Software will share deeper insights into bridge security models and practical risk mitigation strategies.